Invalid Assumptions

My maths background taught me to be very aware of assumptions underlying a given chain of reasoning: some results can't be proven if you don't have some assumptions, and so on. Then all mathematical results are of the form "if X and Y hold, then Z follows". Central to 'evidence based medicine' is statistical analysis. One needs to be aware of all the assumptions underlying such an analysis, and to what degree they hold in practice. A mathematician might be trained to do this, but people with medical backgrounds can easily be oblivious to such things, just blindly assuming the mathematical techniques in their textbooks work, and applying them under the implicit assumption that they do work.

Not Comparing Like With Like

Probably the central invalid assumption is this:

- Same diagnostic label → same disease → same treatment.

This breaks into two parts

- Same diagnostic label → same disease;

- same disease → same treatment.

The trouble with 'same diagnostic label → same disease' is that without it, if one collects together people with the same diagnostic label, we don't know that we are comparing like with like. It's like grouping people based on whether the discomfort is in the torso or the head, and ignoring any other specifics as to what sort of pain it is.

Then the trouble with 'same disease → same treatment' is that without it, it makes no sense to trial treatments on people with the same disease and apply statistical methods to work out what is an effective treatment. The statistics analysing a randomised clinical trial assumes that the results are independent of how the patients were randomised to groups. Then, when a clinician is in a 1-on-1 situation with a patient, they no longer know where that patient is with respect to the 'average patient' that the trial's analysis gives results about. If you trial treatments for torso pain, and 99% of those are stomach ache, and 1% angina, you'll fail to find effective treatments for angina, and you will just observe an occasional failure of treatment or adverse outcome, and just say that "the treatment for torso pain usually works but doesn't always" and angina would be termed a "treatment resistant torso pain".

Assuming Bipolar = Bipolar

It is easy to believe, given that it has its own entry in the diagnostic manual, that bipolar is a single thing which all bipolar 'sufferers' have in common. Likewise they assume that if someone has two episodes of mania, they've had two of the same thing. And then they assume that if two people each have an episode of mania, they've had the same thing.

I've not seen anything evidence-wise which supports these assumptions. The sheer astronomical scale of the brain's complexity, the almost-unimaginable number of qualitatively distinct ways of wiring the 80 billion neurons in our brain, means it's highly unlikely that these assumptions hold. You should expect that the number of qualitatively distinct ways in which a brain can malfunction is significantly greater than the number of living human beings on the planet.

Without these overly simplistic assumptions, most stuff like clinical trials of treatments for mania are very limited in what can be confidently inferred from them. Mania is as broad a category of problems as 'overheating' or 'combusting'.

Consider fire:

- Just knowing that there is a fire in a building is not enough to infer what caused it.

- And if a building has two fires it is not safe to assume that they were both the same type of fire with the same cause.

- And if two different buildings each have a fire it is not safe to assume that they were the same type of fire caused in the same way.

- And of course it is not safe to assume that two different fires can be 'treated' (i.e. extinguished) in the same way (compare a wood fire to a chemical fire to an electrical fire).

Medical psychiatry makes the major mistake, almost oblivious to it, of assuming without justification that the brain and its behaviour is many many orders of magnitude simpler than it is. Without such assumptions, a diagnostic manual like the DSM which categories according to gross symptom patterns (e.g. mania, or hearing voices), and then researchers who group cohorts according to these overly-broad diagnostic categories thinking that they can seek a common remedy for them all, is unworkable.

Sure, if someone is in a major acute mania, you need to dampen their brain, much as you need to starve a fire of oxygen and bring the temperature to below that at which combustion takes place. But once that 'acute phase' work is done (which is where meds are the right thing to use), for the rest of it you have a long complicated road of interactive problem solving.

I abbreviate this to the absurd looking 'bipolar ≠ bipolar', which is really short for 'my bipolar ≠ your bipolar', and likewise 'mania ≠ mania' being short for 'one episode of mania ≠ another episode of mania', and similarly 'autism ≠ autism'. Then the idea that my bipolar as it is today is the same thing it was ten years ago is again an implicit assumption that medically minded people take on, usually without realising it.

As to the above considerations, to borrow their term, they 'lack insight into the limitations of their model of clinical reasoning'.

Calling Bipolar 'it' in Singular

To reiterate the above, I've often heard 'It is treatable'. My thoughts are this: "It"? As in "bipolar is a single well-defined thing which all bipolar sufferers have in common", and "if Jack has bipolar and Jill has bipolar, then they both have the same thing"?

It may be better to talk of 'bipolar disorders' (plural), and 'Jack has a bipolar disorder' and 'Jill has a bipolar disorder', and 'often this drug reduces the incidence of mania in people who have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder', rather than 'this drug effectively treats bipolar'.

It's a subtle distinction, but I think a crucial one, and one which undermines much of the 'evidence' base for common 'evidence-based treatments'. The 'evidence based medicine' paradigm is fine when you can neglect the complexity of the brain: it works when problems occur at the level of individual neurons, where the particular configuration of neurons in a brain can be safely ignored; it is prone to failure once things become sensitive to the particular configuration of neurons which make up a person's brain; and the sheer number of possible qualitatively distinct configurations of neurons (even given the assumption that such a person has learned to live in modern society), it is basically impossible to get sufficient people to have a 'representative sample' of possible qualitatively distinct neuron configurations, and so any statistical methods and results which assume that a sample is representative no longer apply. A subtle thing, I know, but something my maths and mathematical logic background drilled me into being aware of: if you cannot assume that your sample is representative, what statistical inferences can you actually reliably make?

Assuming Independence of Variables

Consider first a classic Etch-a-Sketch:

It has two knobs. One moves the point vertically, one horizontally. If you turn the horizontal knob, where the point is vertically is unaffected, and vice versa. If you turn the horizontal knob 10°, and then turn the vertical knob 20°, the result is the same as if you turn the vertical knob 20°, and then turn the horizontal knob 10°. You can control horizontal and vertical independently. When it comes to doing maths, this independence of variables and commutativity can be very convenient and useful.

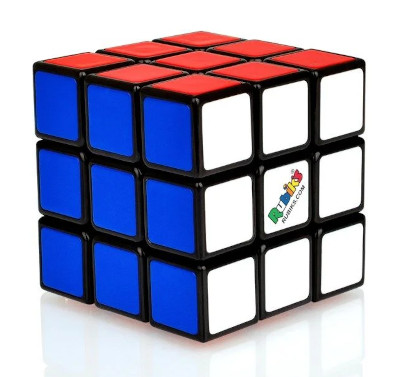

Now consider a classic Rubik's cube:

Here things are not so convenient. We cannot move an individual cubelet where we want: we have to move a eight at a time in a particular way. Then if we say turn the left face, then the top face, the result is not the same as turning the top face and then the left face. It is far harder to get the Rubik's Cube to a desired arrangement than it is to draw a few lines with an Etch-a-Sketch.

When it comes to Mind and psychiatry, things are complex and intertwined, like the Rubik's Cube, and unlike the Etch-a-Sketch. (Though the Mind is way more complex than the Rubik's Cube, and problems can be harder to solve and more frustrating.)

When it comes to, say, treating 'mania' or 'hearing voices', if we simply think in terms of 'treating mania' without considering the myriad other consequences of applying a particular treatment (and this goes way beyond what is normally considered 'side-effects'), the treatment may have many undesirable consequences. If we 'treat mania' more strongly, then even though from a 'solving the mania problem' perspective (if we simply observe incidence rate and intensity of 'mania' and ignore everything else), what appears to be the best 'evidence based treatment' may not be the best treatment for a particular individual.

When treating an individual, we need to consider the person as a whole, and cannot consider the 'mania' independently from the rest of their life. It is very inconvenient from a treatment and research point of view, and so often the 'evidence based medicine' paradigm implicitly assumes that the variables they are dealing with can be optimised independently from the rest of the patient's life. When it comes to chemicals affecting the brain, this is probably never the case. Rather, treating 'mania' in one particular way will hopefully exchange one set of problems for another set of problems which is easier to solve, rather than the treatment making a particular problem (the 'mania') go away without affecting anything else. And of course when it comes to 'measuring outcomes', as 'evidence based medicine' naturally does, all those myriad other variables in a person's life distinct from the 'mania' that one is researching treatments for, get silently discarded, averaged away by the statistical processes used. Then, when a clinician faces a patient in a one-on-one setting, not only are they often unaware of what information has been thrown away in the analysis processes that 'evidence based medicine' utilised, they have no practical way of putting that information back. Thus the results of things like clinical trials can only hint at what may be useful: all else must be determined on an individual basis by the individual clinician. (Then there is the Talking To A Fish problem, from the perspective of the patient.)